Day trips spark the spirit of possibilities. We imagine alternative lives lived in neighboring towns just down the road.

Curiosity – even if just for a few hours – renews. Here’s a Chalone AVA Field Trip and what you need to know about this beautiful AVA.

Where Is Chalone AVA?

In pandemic-fueled “have-to-get-out-of-the-house” road-trip fashion, a recent jaunt took us on an afternoon tour down the Salinas Valley and through the Chalone AVA in Soledad, CA.

Soledad is a rural agrarian community that’s seen an up-tick of out-of-towners since their local National Monument, Pinnacles, became a National Park back in 2013.

If you’d like a fuller sensorial experience, consider tuning in to one of the regional stations, Tricolor.

Or, take a moment to listen to this fabulous song “Tú Ya Eres Cosa Del Pasado” – or “You’re already a thing from the past”

But I digress…

What’s Chalone AVA Like?

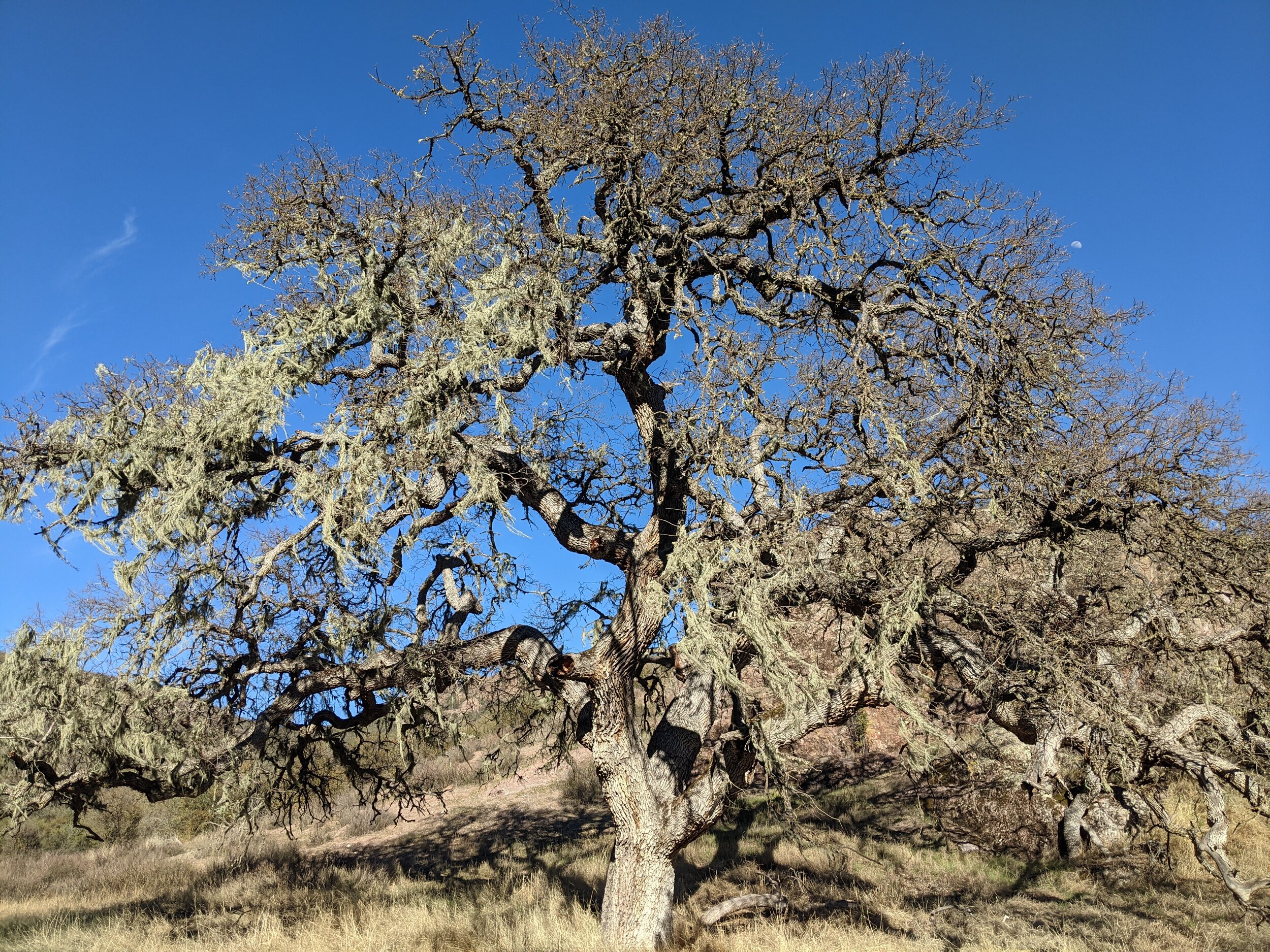

February on the Central Coast dresses itself in grey – baren oak trees, or ‘robles’ in Spanish, and dried fields blend together with little color from muted winter sunlight. Hillsides are just beginning to wake up with fresh green shoots from our welcomed and much-needed rains the other week.

Chalone AVA Regional Data Points

The Chalone AVA, approved in 1982, overlaps both Monterey and San Benito counties for a total area of 8640 acres, with only around 300 acres under vine. Chalone, named after local mountain peaks, nestles itself in the Gabilan Mountain Range, which runs North – South on the Eastern side of the Salinas Valley.

Originally, the AVA was to be called “The Pinnacles”, but changed to Chalone through the open comment period with the TTB.

The first recorded evidence of the name “Chalone” goes back to 1816 and refers to a branch of the Costanoan American Indian family.

North and South Chalone Peaks border the AVA.

Soils: From the earth…

Chalone’s soils are a key defining feature. Decomposed granite and limestone make this a perfect home for Burgundian and Northern Rhone varietals – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Syrah thrive in the shallow, well-draining soils.

What’s So Special About Granite Soils and Wine?

Granite’s magic comes from its formation and decomposition. An igneous rock formed under heat (magma) and pressure, granite has a coarse, crystalline texture – you can see the individual minerals in granite – super obvious in any polished granite countertop. The rock is mainly composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica.

This trifecta is the secret sauce.

The mica crystallizes first, followed by feldspar, and finally the quartz. Remember, all of this happens deep inside the Earth’s crust under heat + pressure.

Over time, the granite moves from the crust to the surface through natural erosion or – in the case of Chalone – tectonic activity.

The infamous San Andreas Fault runs through the AVA.

Earthquakes pushed our granite up to the surface. When exposed to the elements, granite’s components decompose inversely to their formation.

First micas and then feldspars break down into clay, finely grained and slowly sifting through the soil to form a subsoil that has the ability to capture and retain water throughout a dry growing season.

The process of decomposition leaves well-draining, loose quartz crystals as topsoil, encouraging vine roots to reach for water and nutrients.

Other Winegrowing Regions with Granite Soils

Other world-famous wine-growing regions with granite? France’s Northern Rhone, Beaujolais Crus, the famous hill of Hermitage.

Over in Spain we have Rías Baixas with their biting Albariños, along with their nextdoor neighbors, Vinhos Verdes, along the Minho River in Portugal.

Down in South Africa the Paarl Mountain stands as a monument of weathered granite, along with Stellensbosch.

Then in Australia we have … wait for it … the Granite Belt of Queensland.

Okay, But What About Limestone Soils?

Glad you asked. Limestone… Also a boon to the vine.

Limestone retains water in dry climates and contains high levels of calcium carbonate. Calcium-rich soils help with nutrient uptake thanks to their positively charged ions.

Root hairs are negatively charged. The two attract each other and the charge helps the vine to absorb minerals, ions, and other molecules.

Calcium also acts to protect the acidity in the grapes through the ripening process, acid that’s responsible for vibrant and age-worthy wines.

Chalone’s limestone comes from millennia of marine life forming layers of sediment.

Each ice age and subsequent warming period brought the ocean shores inland, rising and receding, leaving behind limestone-rich layers of marine material.

Fertile ground for happy vineyards.

Chalone AVA: Climatically Speaking…

Chalone sits at 1,400 – 2,000 ft., rising above the marine fog line that tumbles in from Monterey Bay during the summer (fog sits at about 1,000 ft.). Because the vineyards are unprotected from the fog, this leads to a wider temperature shift than growing sites located at lower elevations.

Temperature swings help vines to cool down and recover from searing daytime highs, leading to greater phenolic development and better acid retention.

Insider’s Advice: Pinnacles can reach temperatures over 100℉ during the summer, plan accordingly if you’re thinking of a visit to the National Park.

Chalone AVA is off on the East side of Highway 101, so not the most trafficked wine region. Chalone Vineyard leads as the most well-known producer in the region with a local tasting room, followed by Michaud.

Thirsty visitors take heart!

Chalone AVA sits along Monterey’s River Road Wine Trail, so still, plenty of other wineries to explore on your day trip. Many regional labels source fruit from Chalone.

Chalone AVA Day Trip Discoveries

Lots of new vineyard development happening. You’ll pass austere industrial vineyards and smaller family lots. All waiting for spring.

Final Thoughts – Until Springtime in Chalone AVA

Thirsty for More?

Check out my favorite wine tasting on Cannery Row, great for locals and visitors alike.

Here’s why Monterey grows amazing wine grapes.