At some point in everyone’s wine journey, they run into cryptic references of phylloxera. What is it and why is it such a big deal?

Phylloxera is an aphid-like insect (a louse) that feeds on grapevine roots, killing the grapevine. The insect traveled from Eastern North America to Europe, devastating vineyards in the late 1800s. The only known prevention is grafting phylloxera-resistant American grapevine rootstock onto European grapevines (aka Vitis Vinifera – e.g., Merlot, Chardonnay, etc.). Despite knowing the prevention for almost over 100 years, phylloxera was an issue for grape growers in California as recently as the 1980s.

Here’s what you need to know about phylloxera.

- Grapevine Phylloxera: The Devastatrix

- When Was the Phylloxera Outbreak?

- How Did Phylloxera Affect Europe’s Wine Industry?

- How Do You Prevent Phylloxera in the Vineyard?

- Are All Wine Grapevines Grafted? No

- Is Phylloxera Still a Problem?

- Want to Learn More about How Phylloxera? (One of my favorite wine books)

- Thirsty for More?

Grapevine Phylloxera: The Devastatrix

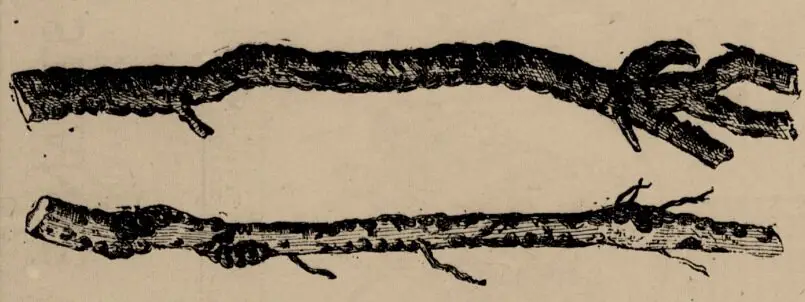

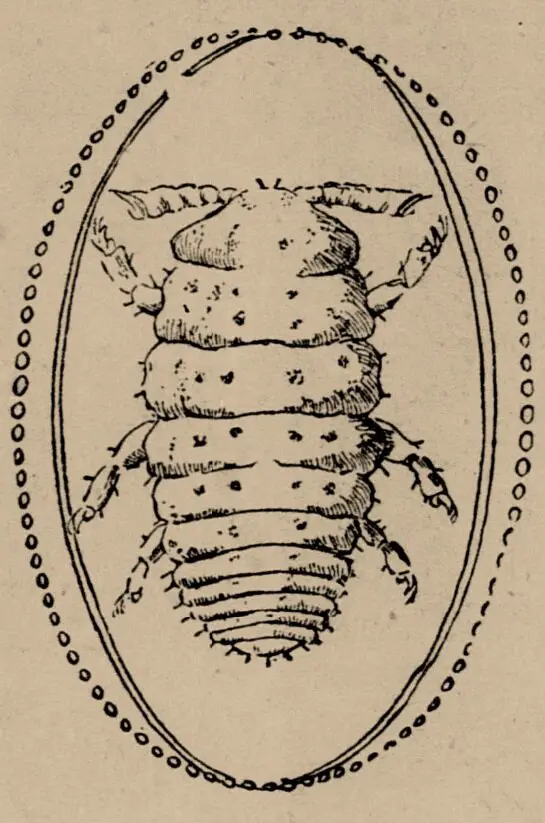

Phylloxera (pronounced fell-OX-era) is a tiny louse that eats grapevines. Naturally found living on the native grapevines in the eastern North American continent, phylloxera and the vines evolved together over millennia in a symbiotic relationship.

Phylloxera goes through a complicated lifecycle where sometimes it lives down by the roots and other times it’s on the vine leaves.

When Was the Phylloxera Outbreak?

In the late 1800s, about 150 years ago, phylloxera began to spread. Botanical enthusiasts unwittingly transported phylloxera to Europe, Australia, and even the western US.

Why?

Shipping exotic plants to share with friends and family was all the rage back in the day (Victorians, go figure?), and among their sea-born specimens were cuttings of native American grapevines.

Not just the vines made the journey, but also stow-away insects.

From greenhouses and garden plots in France, phylloxera systematically marched across Europe through the early 1900s, effectively decimating the winegrowing industry.

European grapevine species, or Vitis vinifera, didn’t have the natural immunity to phylloxera. Every vine affected by phylloxera died.

How Did Phylloxera Affect Europe’s Wine Industry?

As France’s wine production fell, lesser-known regions rose up to take its place with a few unexpected results.

Result #1: Winemaking Spread

First, skilled French winemakers and viticulturalists migrated to areas as yet unaffected by phylloxera.

This had a net-positive effect, improving local wine growing and winemaking expertise wherever French workers moved to make wine.

Fun Wine Fact: The phylloxera crisis led to French winemakers and winegrowers moving to Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and even Spain, helping boost nascent wine industries across the globe. Here’s a fun post on Chile’s Carmenere that touches on this grape’s curious history.

Result #2: Increased Agricultural Commerce

Second, the need to export skilled workers and import wine for a thirsty populace led to increased agricultural and commercial traffic between France and other wine growing regions on newly constructed railroad systems.

Unfortunately, this actually sped up phylloxera’s spread to virgin vineyards around Europe. oops…

The end result was that by 1910 almost no European wine producing region had been left unaffected.

How Do You Prevent Phylloxera in the Vineyard?

The only prevention known to treat phylloxera is root grafting. This simple process takes phylloxera-resistant rootstocks (the bottom root-stem of a vine) from the native American vine species Vitis berlandieri, Vitis riparia, or Vitis rupestris and joins it with the European fine-wine producing species Vitis vinifera (the green leafy part of the plant).

Fun Fact: Horticultural grafting has been around for thousands of years. Walnut trees, almond trees, apple trees – lots of trees use grafting.

Grafting became the panacea for devastated vineyards.

By the time phylloxera hit virgin vineyards around Europe in the early 1900s, the cure was well-known. Grape growers quickly grafted over their vineyards, only losing a few years of production in the process.

Today, nurseries propagate new vines with root grafts that integrate phylloxera, drought resistance, and even tolerance for soil salinity. Yay! Science!

Helpful Tip: Here’s a way more detailed post on grafting rootstocks for wine grapes.

Are All Wine Grapevines Grafted? No

No, not all grapevines are grafted. Own-rooted vines, vines that have never been grafted and are able to grow on their natural root systems, are uncommon but highly sought-after by wine enthusiasts.

A few special conditions make this possible.

Exception 1: Special Sandy Soils

Phylloxera doesn’t do well in deep, sandy soils, and so vineyards fortunate enough to find themselves in these soil conditions can often be own-rooted.

Jargon Alert: Own-rooted is a way to say that the vine isn’t grafted.

Exception 2: Geographically Remote

A few grape producing areas around the world never had the pest imported.

Chile holds the distinct honor of being the only major grape producer globally that never had phylloxera.

The Andean mountains to the west and the Atacama Desert to the north effectively isolated the country from over-land insect migration.

Today, strict quarantine laws protect the Chilean grape industry.

But perhaps the most famous holdout against phylloxera are the vines of Barossa Valley in Australia, still sans phylloxera some 150 years after the bug made landfall on the continent.

Ancient vines planted in the 1890s claim the venerable title of ‘oldest vines in the world’ thanks to their phylloxera-free vineyards.

Today, some Barossa vineyard managers choose to establish newer vineyards on American rootstock hedging their bets against the eventuality of phylloxera’s arrival.

Others believe in the resilience of Barossa Valley’s impenetrable history against the louse.

Helpful Tip: Here’s a post that dives into Barossa Valley’s unique winemaking worth a visit if you love Australian wines.

Is Phylloxera Still a Problem?

You would think that since we know how to prevent phylloxera, it wouldn’t be a problem anymore. But phylloxera’s still around.

Phylloxera’s story is far from over.

AXR1, an infamous rootstock hybrid crossing V. vinifera and V. rupestris, gained popularity in North America as a suitably phylloxera-resistant candidate when grape growers were replanting throughout the 1900s.

The rootstock never performed well in Europe or South Africa, however, and despite warnings to their viticultural cousins across the pond, appeared to have good results in California.

So, vineyard managers planted AXR1 extensively throughout Napa and Sonoma.

Unfortunately, AXR1’s vinifera parentage, that small percentage of vinifera DNA, proved fatal for the vines.

As recently as the 1980s, vineyard owners had to rip up their vineyards and re-plant them with fully phylloxera-resistant rootstocks.

And that, my vinous friends, is a very brief synopsis of phylloxera.

Want to Learn More about How Phylloxera? (One of my favorite wine books)

If you’re really getting into wine, or love a good history read, then you must get this book!

I highly recommend the book “The Botanist and the Vintner”, a historical narrative that takes you back to Europe in the late 1800s. You’ll ride along as phylloxera spreads and follow key players, both viticulturalists, politicians, and botanists as they watch the devastation spread.

A riveting must-read for any wine lover.

Thirsty for More?

Check out this post that covers how they come up with the price for a bottle of wine you see at the store.

Here’s a post that goes into how they decide what grapes to plant where.