When you’re looking at the price of a bottle of wine on a store shelf, no doubt you’ve asked yourself: How did they come up with that price?

The price you see on a bottle of wine starts with factors back in the vineyard and works its way through production and distribution. Costs related to growing grapes, making wine, bottle design, marketing, and shipping wine all influence price.

Here’s what you need to know about what goes into the cost of wine.

TL;DR: This is a long post because I want to be thorough – If you just want to skim this post and look at the graphics, you can see what will increase wine bottle costs and what will decrease wine bottle costs under each factor. Easy!

- The 8 Key Expenses in Wine Bottle Price

- Wine Bottle Price Factor 1: Grapes

- Wine Bottle Price Factor #2: Winery Operations

- Wine Bottle Price Factor #3: Packaging Costs

- Wine Bottle Cost Factor #4: Routes to Market (getting the wine to you)

- Wine Bottle Cost Factor #5: Currency Exchange Rates

- Wine Bottle Cost Factor #6: Government Tariffs

- Wine Bottle Cost Factor #7: Government Taxes

- Wine Bottle Price Factor #8: Retail Markup

- Summary: Why Does a Bottle of Wine Cost What It Does? #REASONS

- Thirsty for More?

The 8 Key Expenses in Wine Bottle Price

The bottle price you see at the store or on the restaurant menu has 8 major factors influencing it. These price factors are:

- Grapes & Farming

- Winery Operations

- Packaging

- Routes to Market

- Currency Exchange Rates

- Government Tariffs

- Government Taxes

- Retail Profit Margin

Every vineyard, every bottle, and every market is unique. Your market for wine will be different than my market for wine. Added to the complexity, every vintage will be different.

Example: A year when there’s a bad frost that kills vines and means fewer grapes for sale will have wineries competing for a limited quantity of grapes which can increase costs (supply and demand).

Because of this nuance, I’ve broken down the cost factors that will increase or decrease bottle price.

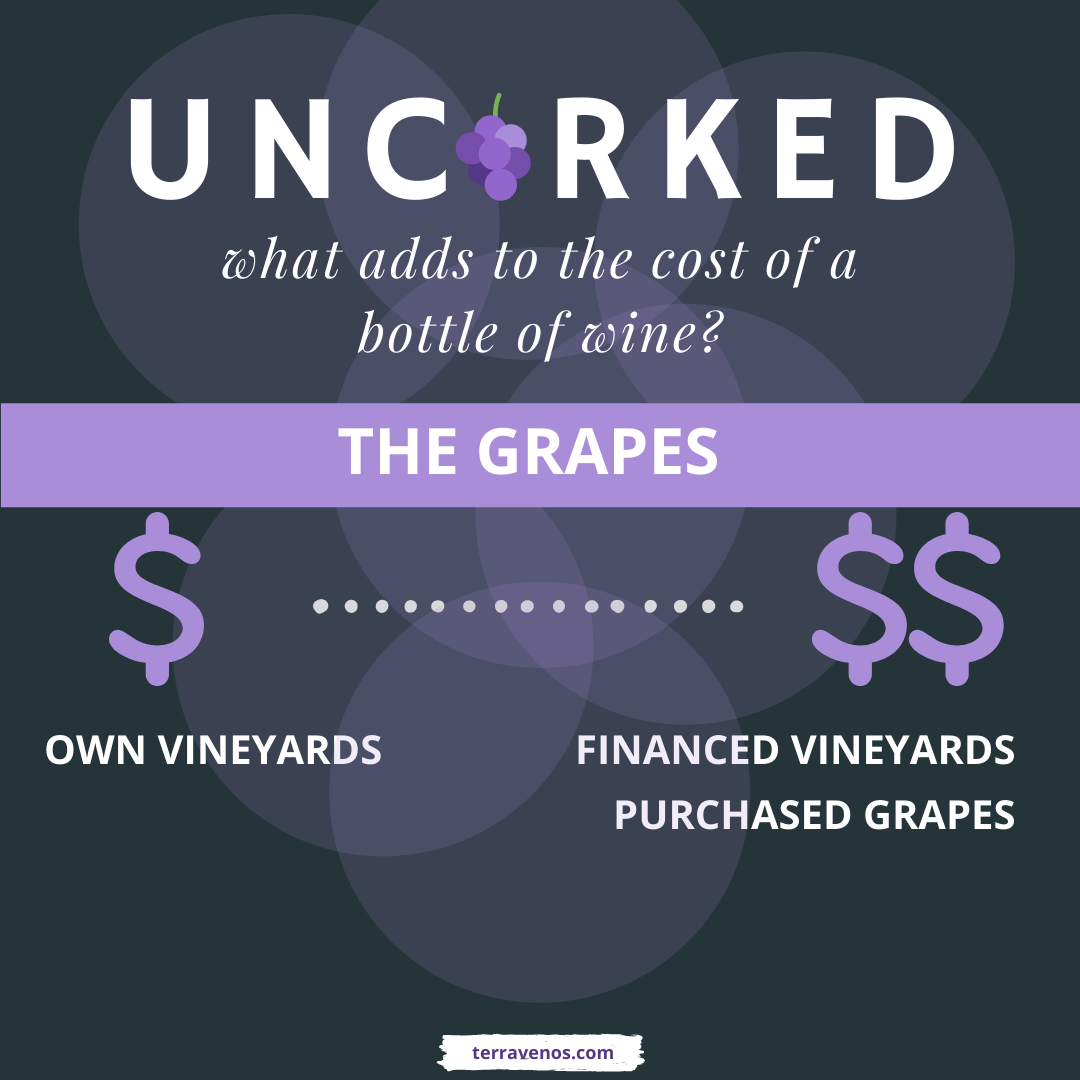

Wine Bottle Price Factor 1: Grapes

The cost for grapes gets broken down into 2 subcategories:

- the land costs

- farming costs

Land Costs: Where Do You Get Your Grapes? Own vs. Finance vs. Contract

Just like you have options when it comes to your living arrangements, producers have options when it comes to getting their hands on grapes.

- Owning the land

- Financed vineyards

- Contract grapes (buying someone else’s grapes)

Grapes are one of the most significant overhead costs of making wine. Producers have three possible routes to fruit.

- Owning the Land: Here, the producer owns the land outright with no loan payments or additional overhead due. This is more common in well-established grape-growing regions. Think of multi-generational operations where the land has been in the family for decades if not centuries. There’s no additional overhead in terms of land costs.

- Financed Vineyard: In this scenario, the producer took out a loan to finance a vineyard holding. This may be for an established vineyard or could be for a new vineyard site. The owner will need to pay back the loan with interest, and that overhead cost gets rolled into the bottle of wine.

- Contract Grapes: Here, the producer goes out onto the grape market and purchases the grapes from someone who owns a vineyard. This could be fresh grapes or even bulk wine. The producer can enter into multi-year contracts with a grower or look for grapes on the spot market.

There are no added direct overhead costs for the land or farming, but whatever the grower’s overhead happens to be will get passed along in the final grape price.

In regions where land and farming are less expensive, the grapes will be cheaper to buy on the spot market.

Regions like Chile and Argentina have access to less expensive grapes. Regions like Napa will have much more expensive grapes.

In places where land and labor are more expensive, the grapes can fetch kingly sums.

Case Study: A ton of Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon can cost upwards of an eye watering $8000 USD. A ton of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from South Africa will come in at a much more palatable $1,000 – $1,200 USD.

Both Napa and South Africa make super-premium, 90+ point Cabernet Sauvignon; the price per bottle will vary starting with overhead costs for the land.

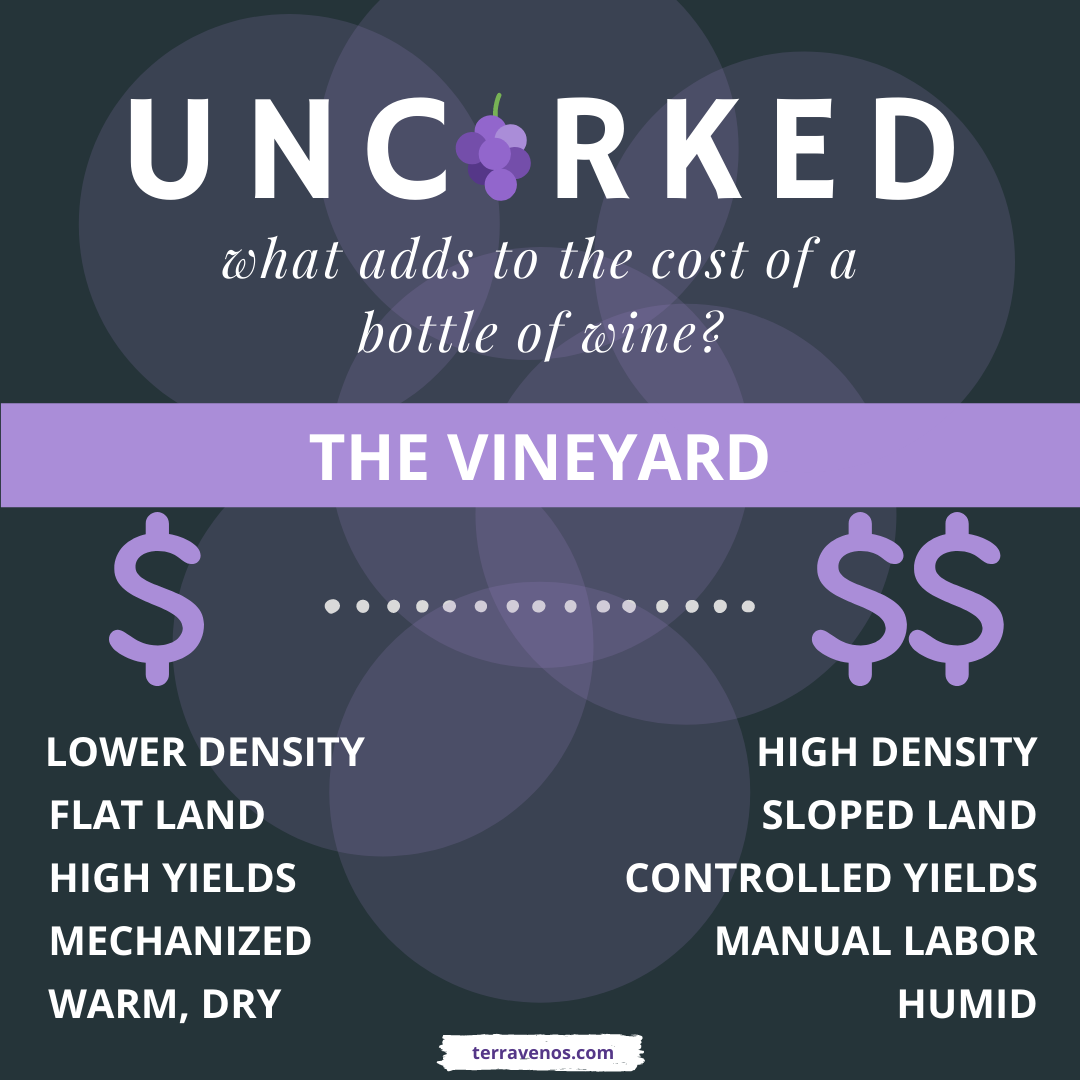

Farming Costs: How Vineyard Practices Affect Wine Bottle Price

Every vineyard has unique costs associated with farming the land. Here’s the breakdown:

Planting Density

Planting Density: Planting density refers to the number of vines on a parcel of land.

Prime property, like a coveted acre of Napa’s Oakville AVA or Bordeaux’s Margaux AOC, will squeeze in every last possible vine on that acre to take advantage of the land.

Of course, the viticulturist will determine the optimal density to encourage fine wine grapes, but every square foot that is capable of having a vine will have a vine on it to maximize land use.

Vineyards with more vines require more resources and are more expensive to own.

Wine growers will need to spend more time in vineyards with more vines throughout the growing season to do vineyard-ey tasks, like shoot thinning, green harvesting, and monitoring for insect issues.

If done by hand, this will increase labor costs.

Flat vs. Sloped Land

Vineyards that sit on flat sites can be machine harvested. This reduces labor costs overall. The vineyard owner can rent a mechanical harvester to bring in the grape harvest quickly.

Some regions, like Priorat DOQ in Spain or the Mosel in Germany, are famed for their terraced and steeply sloped growing sites.

There’s actually an official term for steeply sloped vineyards: Heroic Viticulture.

The Centre for the Heroic Viticulture defines these vineyard sites as:

- Vineyard sites at altitudes over 500 meters (1600 feet).

- Vines planted on slopes greater than 30%.

- Vines planted on terraces or embankments.

- Vines planted on small islands in difficult growing conditions.

While these sites may be great for the vine in terms of maximizing sun exposure and drainage, it means that the vineyard needs to be worked by hand, from pruning to picking and everything in between.

Steeply sloped vineyard sites also suffer from erosion, adding to vineyard maintenance costs.

All of this will translate into your bottle price.

Chemical Inputs

No one likes to think about fertilizers and fungicides when it comes to their boutique bottle sitting so stately on the dinner table, but it’s a fact of life that the vast majority of wine grapes require some form of chemical input in the vineyard. These may be organic or inorganic herbicides, fungicides, and pesticides.

Regardless of what the grower actually uses, each pass through the vineyard adds to production costs.

- Grapes grown in warm, breezy, dry conditions (picture spring break weather) have the added benefit of needing fewer (or no) passes through the vineyard thanks to less disease pressure. This means lower growing costs.

- Grapes grown in regions where there’s more humidity, for example along a river or lake, require attentive viticultural practices, including additional passes with fungicides, to prevent the berries from spoiling before harvest. This means higher growing costs.

What does this look like in practice?

Regions like the Dão or Alentejo in Portugal enjoy a growing climate that’s perfect for organic viticulture requiring fewer passes through the vineyard.

Growing regions like the Finger Lakes, NY, or the Niagara Peninsula, Ontario will need significant inputs to stave off bunch rot from fungal disease.

Each pass through the vineyard adds labor costs, vehicle maintenance costs, fuel costs, and spray costs.

Controlling Yields

A vineyard’s yield is how much fruit it grows. Grapevines are vines, meaning they’re constantly growing.

Vines want to put out green shoots and leaves just like any other vine.

Vigorous vines can produce gobs of fruit for inexpensive wine.

Take Carignan, a robust variety grown throughout Spain and France that will pump out upwards of 200 hectoliters/hectare (5,200 gallons/2.5 acres) if it goes unchecked.

This vigor, however, results in wines with low aroma and flavor concentration – i.e., mediocre booze.

Compare that to Nebbiolo DOCG wines, the wine of kings in northeastern Italy, where growers are capped at 55 hectoliters/hectare (1,479 gallons/2.5 acres).

Rivers of everyday wine fill a market niche. Sometimes we just want a cheap bottle of wine.

The producer won’t make much money per bottle but will have more wine to sell than a producer who restricts the vine’s yields but aims for better quality wine at a higher price point.

This is the quantity/quality question every wine producer needs to balance.

Summarizing Land Farming Costs: Wine Bottle Price

If you’re holding an inexpensive bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to grape growing:

- The grapes come from a flat vineyard site.

- The vines produced a lot of fruit.

- The farming was largely mechanized to limit labor costs.

- The vineyard land was owned outright by the producer or resides in a region where vineyard land is relatively inexpensive.

- The vineyard wasn’t located in a humid growing environment with high-disease pressure.

If you’re holding a pricier bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to grape growing:

- The grapes come from a sloped vineyard site that limits mechanization.

- The vineyard manager restricted vine yields to increase wine quality.

- The farming was largely done with skilled manual labor.

- The vineyard land is financed or located in a highly-acclaimed growing region with a strong reputation for super-premium wines (e.g., Oakville AVA, Napa Valley or Pauillac, Bordeaux).

Wine Bottle Price Factor #2: Winery Operations

Similar to farming and the land, winery operations can be subdivided into 2 categories:

- The winery’s business model

- Wine style and winemaking costs

Winery Business Model

Wine needs to be made somewhere. Like a winery. Wineries come in all different forms – from small, boutique family affairs, to giant multinational portfolios, and even local cooperatives. Each model has different operating expenses and overhead costs that contribute to your wine bottle price.

Cooperatives

Since the 1860s, regions with small vineyard holdings have pooled resources together and given their grapes to a local cooperative. The cooperative was responsible for making the wine and then a) giving it back to the grower to sell or b) selling the wine to a distributor or retail outlet.

Co-ops still exist throughout the winegrowing regions of the world. In a big way.

CAVIRO (Italy – over 260 million bottles/year) and FeCoViTa (Argentina – over 5,000 grape growers) are massive cooperatives that distribute wines internationally.

Giant operations allow economies of scale that aren’t possible with smaller operations.

Large Wine Companies

Arguably, economies of scale and cost savings is also true for privately owned companies that have large-scale operations: Accolade, Sogrape, E & J Gallo, Treasury, and [yellow tail] all capitalize on efficiencies in their production and supply chains that small producers can’t leverage.

These companies have access to cutting-edge resources and equipment that can reduce overhead, whether it’s water treatment plants, reclamation ponds, solar infrastructure, owning supply chains, or even shipping networks.

Lean and mean production facilities reduce per-bottle overhead.

It’s hard to make judgment calls about production facilities for pricier bottles of wine (large producers do make expensive wines), but you can certainly make some safe assumptions when it comes to inexpensive wine.

If you’re holding a cheap bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to winery operations:

The wine was likely made in a facility that produces large volumes of wine.

- The wine likely comes from a sizeable, well-established producer.

- The producer probably controls their supply chain (or very large parts of it).

Wine Style and Winemaking Costs

As for the available winemaking options for inexpensive or premium wines, they are as varied as the wine styles themselves.

The big expenses in wine production are oak wine barrels and maturation (the time between when the wine is finished fermenting and released for sale).

Helpful Tip: Here’s a post that’s a little geeky but covers wine fermentation basics.

Significant Winemaking Cost #1: Oak Barrels

Some wine styles benefit from more costly winemaking methods.

Oak barrels used for fermentation or maturation add to the per-bottle cost.

Less expensive wines may see some oak influence from oak barrel alternatives: oak staves, chips, or dust to keep costs down.

Helpful Tip: Here’s an in-depth post on the history of oak barrels and wine, which you may like if you enjoy oaked red wine – and exactly how much you’re paying per-bottle for oaked wine.

Significant Winemaking Cost #2: Maturation

Maturation is essentially time: How long does the wine need to age at the winery before it’s ready for sale? The faster you can make wine, the faster you can sell it and recoup your expenses.

Wines that need to be aged and matured in the winery for a significant period of time before distribution will have a markup. The producer is essentially sitting on inventory waiting for it to be sellable.

Some wines are held back for years – YEARS – before release.

Grand Reserva Rioja takes its sweet time percolating back at the winery, 5 years to be precise.

Imagine holding onto inventory for half a decade before seeing any return on investment.

In contrast, a producer will vinify, settle/clarify, filter, and bottle an inexpensive wine as quickly as possible.

This maximizes profit flow.

Summarizing Winery Operation Costs

If you’re holding an inexpensive bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to winery operations:

- The wine was made by a large producer that can leverage efficiencies of scale.

- The wine was made to get to market quickly.

- The wine was not matured using expensive winemaking options, like oak barrels, but maybe saw oak staves, chips, or dust.

If you’re holding a pricier bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to winery operations:

- The winery may have been made by a smaller, more boutique producer that can’t leverage efficiencies of scale.

- The wine was matured for a period of time back at the winery before release.

- The wine may have been matured using more costly winemaking options, like new oak barrels.

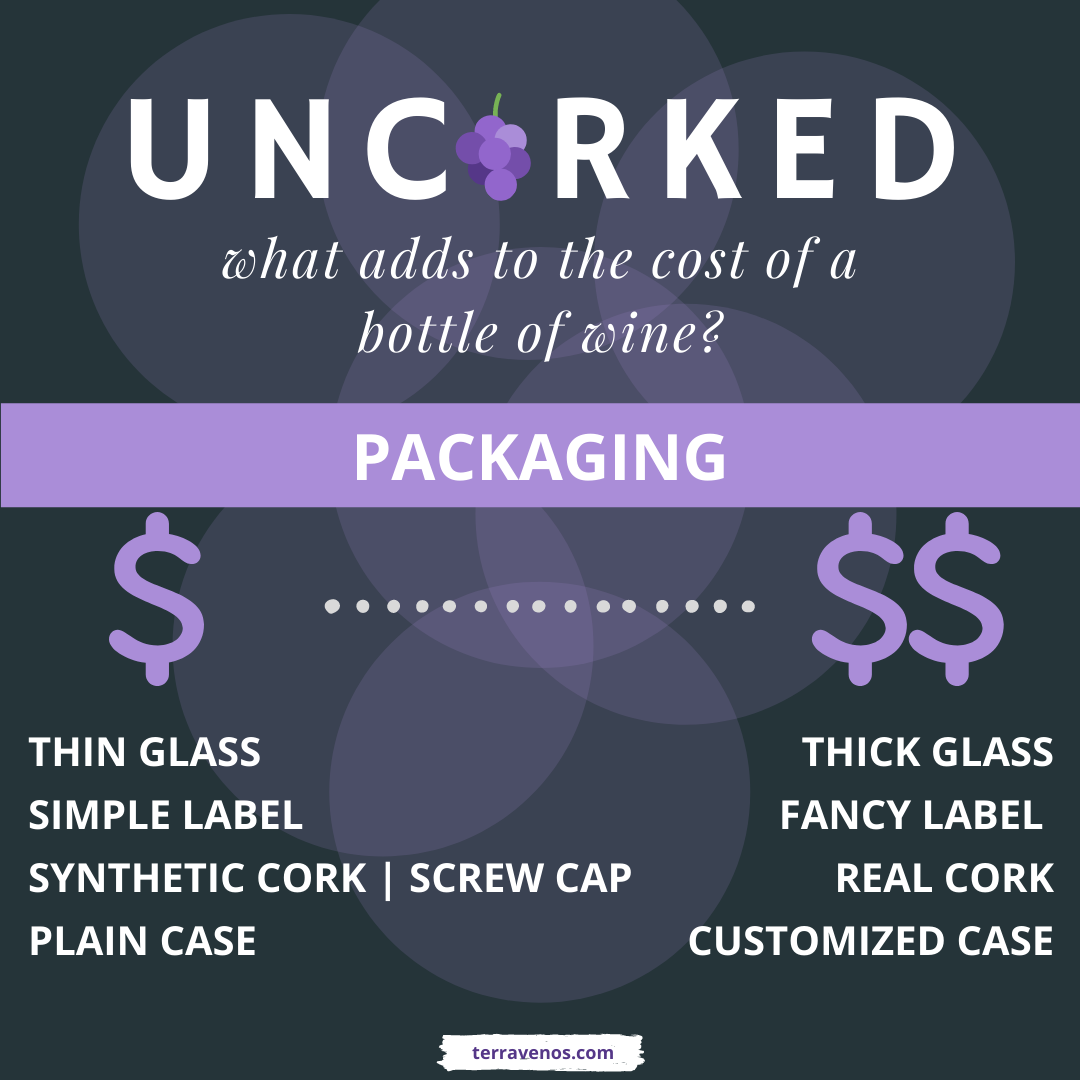

Wine Bottle Price Factor #3: Packaging Costs

Packaging costs for a bottle of wine should be pretty intuitive for most folks.

These are all physical elements you can see when you’re holding your wine bottle, and include:

- bottles

- labels

- closures

- closure caps

- boxes

Each of these packaging options comes in a range of different price points.

Let’s look at each.

Bottles

Bottles vary by style (think a tall, skinny hock bottle for Riesling vs. a stocky Chardonnay bottle), color (flint, clear, or royal blue, anyone?), and weight. This last detail, weight, is a big one.

Consumers subconsciously link the weight of a glass bottle with the quality of the wine inside.

Consumers are willing to spend more money on heavier bottles. Friends always say to me: “just feel the weight of this bottle, Erin – that’s quality!”

Heavier bottles also mean more raw materials to make the bottles and added fuel costs to transport the bottles from the winery to the final retail outlet where you buy your wine.

Heavier bottles will cost you more money.

Fun Experiment: The next time you drink a bottle of inexpensive wine – I’m talking bottom shelf wine that is $5 USD or less, set aside the empty bottle. Then, when you’ve drained a pricier bottle of wine, let’s call it at the$35+ USD price point, take the two bottles and compare their heft. Hold them both at the same time. If you have a kitchen scale you can weigh them side-by-side and physically feel the difference in packaging.

Bricks, Boxs, Cans… Alternative Packaging Is Less Expensive

Alternative packaging will be less expensive. Bag-in-box, bricks, and canned wines require less energy to make and to transport both from the factory to the winery, and from the winery to the store.

Labels

Labels are another expense that gets passed on to the consumer. The label has a functional purpose to list government required information about the wine and the producer.

Outside of that, the label is designed to call attention to the bottle of wine and to help sell it.

Some labels are straightforward. Others are outrageous.

Gilt labels, raised labels, laser-etched bottles, silkscreen bottles – all of these fancy designs add to the bottle cost.

Don’t get me wrong. They are beautiful and can be true works of art, but these details add up.

Closures

Real cork, agglomerated cork, synthetic cork, or screw crap? Real corks are the most expensive closure. Screw caps are less expensive.

Helpful Tip: Some producers add wax to their wine bottles. This adds cost. Check out this short post on the history and purpose of wax (and what it means today).

Closure Capsules: A closure capsule is the piece of tin (more expensive) or foil (less expensive) (or maybe even plastic) that covers the cork.

Sometimes this is embossed with the producer’s logo or even has a gilt impression on it. This adds to your bottle cost.

Obviously, the least expensive route is to forego any kind of capsule.

(Personally, I prefer bottles without capsules because it’s better for the environment. Okay, stepping down from my soapbox now…)

Wine Boxes

These are cardboard boxes that hold 12 bottles at a time, known as a ‘case’ of wine.

Wine boxes, like bottles and labels, come in extremes.

On the one end, you have plain brown cardboard boxes perhaps with minimal printing and a production sticker that indicates the wine inside.

On the other end, you have wooden crates that are etched with the producer’s logo; inside you find bottles wrapped in silk or tissue paper waiting for their moment to shine.

Somewhere in between the two extremes, most boxes come with some sort of design on the outside, perhaps printed with the producer’s logo or a full-on design scheme to match the brand. It’s all part of product marketing.

Summarizing Wine Bottle Packaging Costs

If you’re holding an inexpensive bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to the packing:

- The bottle is thin and lightweight.

- It has a basic label that may have a few select colors to stand out on a shelf.

- It has a synthetic cork or screw cap.

- It has no capsule or only a foil capsule.

- It comes in a standard cardboard box with the product label.

If you’re holding a pricier bottle of wine, chances are most of the following are true when it comes to the packing:

- The bottle is thick and heavy.

- It has a special label that is: 1) silk-screened, 2) gilt, 3) multicolored, 4) some other randomness to make it stand out.

- It has a solid cork.

- It has a tin or foil capsule, or may even be wax-dipped.

- It comes in a customized cardboard box or maybe even a special wooden crate (la dee dah!).

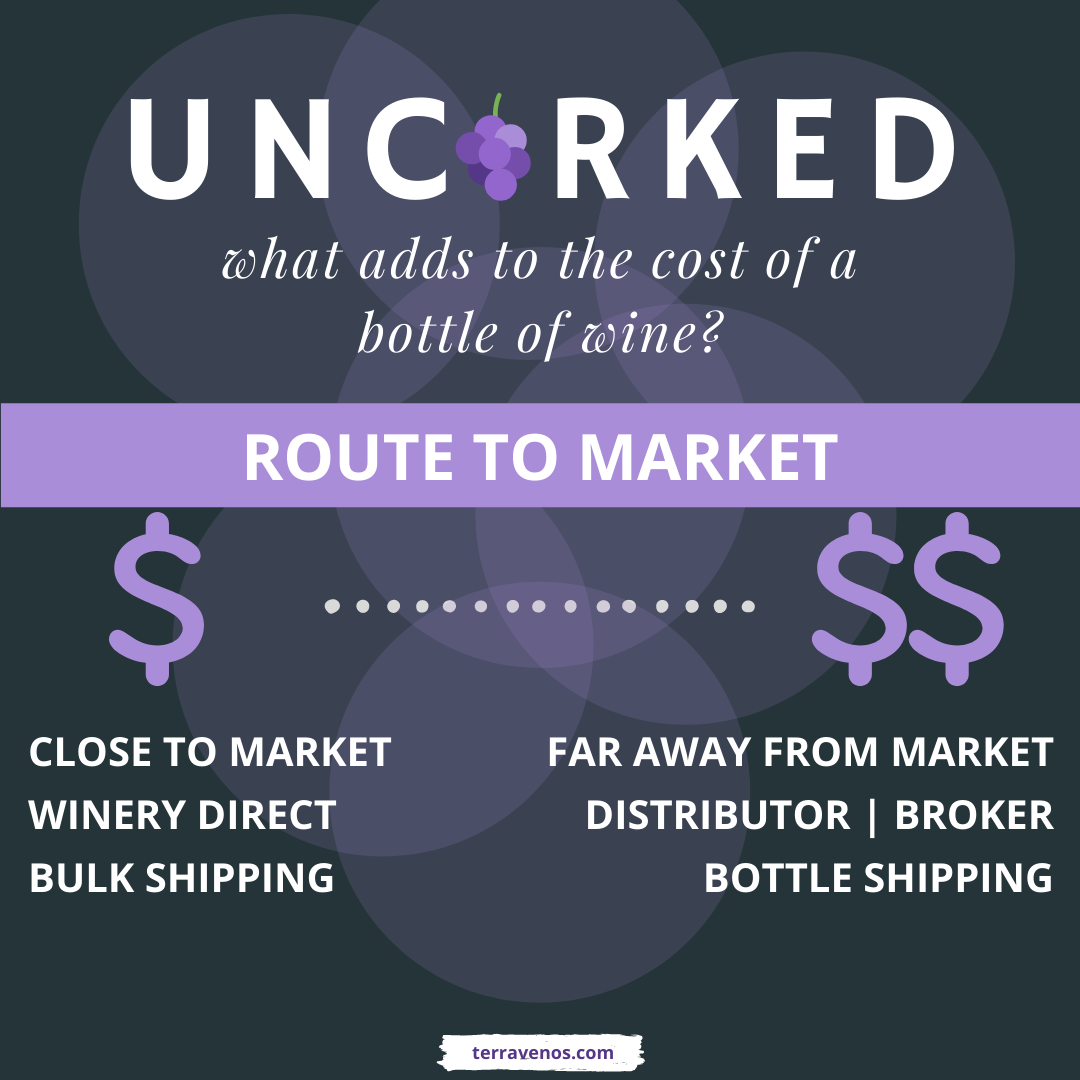

Wine Bottle Cost Factor #4: Routes to Market (getting the wine to you)

Not everyone lives right next to a winery, or even a wine growing region, so most wine needs to get moved from Point A (the winery) to Point B (the place where you buy wine).

Local Wines

Logic dictates that wine made closer to its final market will have fewer logistical and shipping costs.

You’re right. Buying local has less overhead (and is better for the environment – back on that soapbox, again…I digress.)

But…

If you take a weekend trip to wine country and pick up several bottles at a tasting room, you’ll likely benefit from wines priced below what you would find them at a grocery store or liquor store.

You don’t have to pay a markup for the distributor fee or the transportation costs if you buy local or direct.

Helpful Tip: Here’s a good overview post on whether joining a wine club is actually worth it. Definitely a must-read before you head to wine country.

Wine Shipping Costs

But if you’ve ever been a wine club member and had wine shipped to your home or purchased wine online and had it delivered, you know that wine is a heavy, fragile product that’s costly to move from one place to another. In this scenario, the wine club or online wine retailer is passing along the shipping costs to you.

Key Point: Glass is heavy to ship.

So how does shipping work between the wine producer (the winery) and the store or restaurant where you purchase your wine?

This depends on the price point of the wine, where the producer is physically in the world, and where you are physically in the world.

Wine Imports

Large volumes of imported wine coming from overseas will likely be shipped in bulk shipping containers. Once it arrives in the country, it goes to a local bottling facility where it’s bottled and labeled locally.

Bottling in the country where the wine is sold, not where it’s made, cuts down on the transportation costs for glass.

Smaller volumes of wine that cannot fill an entire shipping container and have to be shipped after bottling will have added costs for shipping.

There are pros and cons to shipping full bottles of wine.

One argument for shipping bottles instead of bulk wine is that the producer retains control over the bottling process, which guarantees the wine’s integrity.

A drawback is that glass is fragile and it’s likely that some of the product will be lost in shipping when it breaks.

Also, the wine will lose its freshness faster in the bottle than it does when shipped in bulk volume.

This may or may not be an important factor depending on the style of wine.

Summary Point: Wine shipped in bulk will have a lower markup than wine shipped in bottle.

Once the wine is imported into the country, it still needs to get to your wine shop or restaurant.

This means transporting the wine from the port of entry to a distribution center using freight forwarding via truck or rail to its final destination.

Again, glass is heavy, and at this point, the physical distance between the distribution center and the retail outlet (or restaurant) will add to the cost.

Now, you’d think that the wine would be imported at a port of entry close to where it’s going to be distributed. This isn’t always the case.

Case Study: A French wine may come into the US via the port of Los Angeles and then go by truck or rail back to the East Coast for distribution. It’s not always an efficient system, which adds costs

Who’s moving all this wine?

Alcohol is a weird product. It’s not like a t-shirt or a pair of running shoes that you can pop in the local mail.

Governments regulate the distribution and sale of alcohol in different ways.

In the US, our fractured three-tier system has created a bloated and complicated route to market, where each state has control over the laws governing the distribution and sale of booze.

Wine Brokers & Wine Distributors

Wineries are good at making wine, but not necessarily at selling all of their wine. They work with brokers to find potential buyers.

Brokers know all about the wine market and which buyer is looking for what style of wine. It’s like a matchmaking service… but for wine.

A wine broker will work with the winery to find potential wine buyers (e.g., a restaurant or hotel chain) and help facilitate a contract between the winery and buyer.

Once there’s a contract, the winery needs a distributor to physically move the wine from the winery to the place where it’s going to get sold (a restaurant chain or wine shop). The distributor will move the wine around the country.

Both distributors and brokers take a percentage of the bottle price. This adds to your bottle price.

The US isn’t alone in its web of distributors and brokers.

In France, the Bordeaux wine region enjoys a rich history of working through a similarly complicated distribution network of negociants (distributors).

Each negociant may represent a different commercial interest in different countries around the world.

A producer may work with upwards of 40+ different negociants in an effort to get their wine into all of the venues where they want their wine sold. Negociants enjoy a 15% commission on the final bottle price.

How does the winery find the right negociant?

Why, there’s a broker (aka courtier) who steps in to connect the two. The broker knows who has the wine and who’s buying the wine. The broker collects a 2%-3% finder’s fee on that final price you see on the bottle.

Summarizing Routes to Market Wine Bottle Costs

Upwards of 17%-20% of your wine bottle price is likely going to the distributor, broker, or some combination of the two.

Wine Bottle Cost Factor #5: Currency Exchange Rates

Currency exchange rates will impact imported wine that’s coming into your country from abroad.

Countries with a strong currency enjoy excellent quality for value when they’re importing wines from a country with a weaker currency.

Argentinian Malbec is the classic case study here in the US where currency exchange rates mean less expensive, good-quality wines.

Favorable or unfavorable exchange rates don’t just impact wine imports.

Exchange rates can affect different areas of the supply chain if you’re a producer who has to source supplies or equipment from an overseas market.

Prices for winery equipment (e.g., tanks and hoses), oak barrels, glass bottles, bottle closures, and even cardboard may be sourced from a different country than the country of wine production.

Helpful Tip: I’m serious about Argentinian Malbec – and pretty much any other Argentinian wine. It’s worth exploring for the price point! Check out this post here on Malbec to get started.

Summarizing Currency Exchange Rates and Wine Bottle Prices

If the country you’re purchasing your wine, winery equipment, or winemaking and packaging supplies from has a stronger currency, then that will impact bottle pricing and get passed along to the consumer.

Wine Bottle Cost Factor #6: Government Tariffs

Tariffs are the fees that a government levies on wine imports from abroad. Countries that enter into free trade agreements enjoy lower tariffs on imported goods.

- For example, Chile has a free trade agreement with South Korea for wine imports, making it a prime destination for Chilean wines.

Governments may put protectionist policies in place to help nascent winegrowing regions develop, or tariff hikes can result from trade wars between countries.

It’s not uncommon for wine to be the subject of diplomatic disputes – a proxy battleground for spatting governments.

Case Study 1: Between 2019 and 2021, the US levied a 25% tariff on French, German, and Spanish wine imports. Overnight, wines on container ships waiting to come into a US port we’re taxed at an additional 25%.

Increased tarrif costs were passed on directly to consumers. Ouch!

I remember picking up a bottle of rosé at my local drugstore from Provence at the time and it was $18. That’s an outrageous price to pay for a bottle of rosé. I laughed at the pricing folly and didn’t go home with a bottle of French wine that day.

Case Study 2: You won’t find what would be a mid-priced California wine in the US market over in the French market.

The export costs and currency strength will compel premium pricing in France above the quality level for similarly priced domestic or European wines. It’s not competitive.

Likewise, it’s rare to find premium priced New Zealand Pinot Noir in California. We have too many delicious California Pinots at more palatable prices.

Summarizing Transportation Costs, Government Tariffs, and Currency Exchange Rates

Not all markets will tolerate wines that carry higher prices due to transportation costs, tariffs, and/or exchange rates.

If you ever pick up a bottle of imported wine and think that

- A) it’s great for the money you spent! or

- B) it’s not that great for the money you spent!

You’re experiencing the effects of transportation costs, tariffs, and/or currency exchange rates – or more likely a complicated combination of all three.

Wine Bottle Cost Factor #7: Government Taxes

Governments tax alcohol for good reason. Taxes help deter excessive alcohol consumption and raise money to support social programs.

As of this writing, the US TTB tax rate on a gallon of wine is $1.07 USD, or about $.21 USD/bottle.

States or provinces and local municipalities may levy additional taxes.

In California, there’s a $.04 state excise tax per bottle of wine. So around $.25 of the total bottle price goes to taxes. And there’s an additional 6% sales tax on the total bottle price at the time of sale.

Other countries levy heavier taxes on alcohol.

Alberta, Canada has a flat $3.50 CA tax per liter of wine (about $2.02 USD/bottle).

Ireland levies a €4.87 tax on a bottle of wine (about $5.12 USD/bottle). Gulp!

Summarizing Government Taxes and Wine Bottle Price

A portion of your bottle price reflects government taxes. This depends on where you live in the world.

If you live in a place where there are high taxes on alcohol, you’re probably acutely aware of the taxes you pay for your wine.

Wine Bottle Price Factor #8: Retail Markup

Once the bottle of wine is at the store/restaurant where you’re going to purchase it, then it has additional markups so that the retailer can make a profit.

(The store’s bottle markup is probably what you were thinking about when you started this post, but it’s the last cost that gets added to your wine’s price.)

The wine bottle markup price (external link) will vary depending on the target profit margin for the retailer and this is directly connected to the price the retailer pays to the distributor:

“The conventional retail markup is 11 / 2 times wholesale, or 50 percent; a wine that costs the store $10 a bottle from the distributor might retail for $15. But if you buy a case at a 10 percent discount, that’s $13.50 a bottle. The store then pays credit card fees, including your “cash back” incentives (plus a portion of the profits if you use an American Express card). Those costs eat further into the profit margin. Many small stores today mark up their wines more than 50 percent to help cover the cost of doing business: rent, electricity, employee salaries and benefits. The profit margin can be extremely tight.”

If you’re holding a bottle of wine that’s $15 USD, ~$5 USD will go to the store.

Here’s a rundown of markups ranked from the lowest markup to the highest markup depending on where you’re buying your wine:

- Deep Discounters

- Wineries

- Supermarkets

- Casual Dining

- Specialty Wine Shops

- Quickie Marts

- Duty Free Stores

- Fine Dining

Helpful Tip: Here’s a useful post on how Grocery Outlet can sell their wines for so cheap (Grocery Outlet is a deep discounter in the US that has very inexpensive (but decent) wines.

So, if you’re looking for the best bargains on wine, you’ll want to buy from deep discounters or wineries.

Summary: Why Does a Bottle of Wine Cost What It Does? #REASONS

It’s a complicated (but fun) exercise to try and break down bottle pricing when browsing your local grocery store or specialty wine shop. Here’s what you need to think about:

- Where do the grapes come from? Reputation, land prices, and viticultural and winemaking methods.

- What’s the wine bottle look like? Check out the product marketing, bottle heft, label design, and closures.

- How far did the wine travel to get to you? Do some mental calculations on shipping/transportation distance.

- What are your government taxes like? Think about the tariffs (if any) and taxes.

- Where are you buying your wine? Finally, add in the retailer’s profit margin.

And that, my vinous friends, is how you come up with your bottle price.

Thirsty for More?

If you’re really into the nuances of the wine market, then check out this post on how bulk wine works – it’s not all cheap plonk!

And here’s a rundown on how winegrowers decide on what grapes to plant where, which looks not just at climate, but market demand and what kind of wine they’ll make.