I’m starting to get questions about my harvest plans. This time of year is a lot like late winter for home gardeners – much anticipated glossy seed catalogs arrive in the mail and winter-weary growers start to dog-ear pages, making notes and planning plots.

Winemaking is the process of converting grape juice into alcohol using yeast. There are two main types of yeast used in winemaking: ambient yeast and cultured yeast. Ambient yeast is found naturally in the environment, while cultured yeast is laboratory-grown. Winemakers choose cultured yeast based on the style of wine they want to produce, such as a fruitier, earthier, or higher-alcohol wine.

Here’s what you need to know about choosing wine yeast.

- Wine Fermentation Yeast

- Producers Use Native Yeast for Natural Wines

- When Don’t You Want Native Yeast Fermentations?

- Where Do Cultured Yeast Come From?

- How do winemakers select yeast?

- Wine Yeast Criteria #1: Potential Alcohol Level

- Wine Yeast Criteria #2: Fermentation Temperature

- Wine Yeast Criteria #3: Sulfur and Nutrient Needs

- Wine Yeast Criteria #4: Yeast Killer Factor

- Wine Yeast Criteria #5: Malolactic Bacteria and Yeast

- How to Select Wine Yeast Case Study

- Wine Yeast Selection Criteria #6: Smells, Flavors, Textures

- How to Read Wine Labels for Yeast

- Final Thoughts – Wine Yeast Are the Superheros in Winemaking

- Thirsty for More?

Wine Fermentation Yeast

Winemakers have two basic choices when it comes to yeast: native or cultured.

The main species of yeast used in winemaking, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is the same yeast used in brewing and baking.

These cheerful unicellular critters are responsible for fermentation. No yeast? No wine. They chow down on the grape juice’s sugar, converting it to alcohol, heat, carbon dioxide (CO2), a little volatile acidity, a little sulfur, and wine aromatics.

Helpful Tip: Check out this in-depth post that goes over how wine fermentation works in more detail. Spoiler alert: It’s a little nerdy.

Yeast exists around us, floating through the air and resting on surfaces – waiting for an opportunity to start their lifecycle. If given a food source and the proper temperature, they’ll start reproducing.

Fun Wine Tasting Tip: Winemakers love talking about yeast. If you find yourself with a winemaker, ask about how they select their yeast bonhomies. Guarantee there’s a story.

What Does Native Fermentation Mean?

A native fermentation relies on the ambient yeast living in the winemaking facility or vineyard for fermentation. The winemaker doesn’t add any additions to the crushed grape juice.

Synonyms for native yeast fermentations include: natural, wild, and indigenous.

Natural winemaking that relies on ambient yeast doesn’t always occur with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Other species may dominate the fermentation.

Wineries with longstanding winemaking traditions may depend on indigenous yeast for fermentation. Ambient yeast happily floats around the winery from decades or even centuries of wine production and they will find their way to the new juice without any human help.

Wine has been made this way for thousands of years, so native yeast is certainly a tried-and-true approach.

Natural fermentation purists argue that wild yeast create unexpected complexity in a wine that cannot be replicated with cultured yeast strains.

In addition to complexity, another advantage is cost.

If you add nothing, it costs nothing.

Commercial yeast isn’t terribly expensive, but if the winery operates with small profit margins, every penny counts.

Producers Use Native Yeast for Natural Wines

Winemakers use native yeast for natural wine. The idea behind natural wine is that the winemaker does the bare minimum for intervention, shepherding the juice through fermentation.

Natural winemakers also take advantage of the “native yeast” label for marketing.

‘Natural’, ‘native’, ‘wild’, ‘indigenous’ – all of these labels play to consumers wanting to make healthier beverage choices. Native yeast may be a part of the overall marketing plan for a label.

But wild yeast come with unpredictable risks.

Winemakers don’t know what ambient strain will dominate the fermentation, and certain yeast can create off-aromas and general funkiness. Some consumers enjoy this style. Many do not.

I’m enjoying a light-hearted murder mystery set in a small French town, The Dark Vineyard, by Martin Walker, that narrates an exchange between two characters and perfectly captures natural fermentation.

The characters are Joe, the venerable vigneron, and Jacqueline, a young visitor from Canada.

They’ve just taken a break from stomping grapes:

“Do you add any yeast?” Jacqueline asked.

Joe: “There are enough yeast spores in the walls of this barn to ferment half of all the wine in Bordeaux. So we just leave the yeast to Mother Nature, as our ancestors have for hundreds of years. Come on, I want you to try last year’s wine, get a sense of just what you’ve been helping to make. Bring us a couple of those glasses from the table there.”

He pulled a bottle with no label from a horizontal rack and opened it with an elderly corkscrew with a handle of olive wood. He splashed some of the wine into a glass for each of them and raised his glass.

“To the new vintage,” he declaimed, and then emptied his glass in a single gulp, like a Russian downing vodka.

Jacqueline was staring at the sludgy liquid in her glass. Gingerly, she put her nose close and took a very small sniff. Her eyes widened. She took a sip, swirling it around in her mouth and then spitting it out as if she was at a wine tasting. … She took a small sip, rolled it around in her mouth and swallowed.

“So what do you think of my wine, Mademoiselle?” Joe asked.

“Very authentic. Very true to its terroir, to its maker.”

When Don’t You Want Native Yeast Fermentations?

Damaged Grapes

Grapes that arrive at the winery damaged by pests or fungal rot already harbor significant microbial activity. Not every year may be a good year for native yeast fermentations.

This is bad.

In this scenario, a winemaker will likely opt for a commercial strain to ensure a quick, clean fermentation before the bad microbes take hold.

Over-Ripe Grapes

High alcohol can be another challenge for native yeast. Yeast struggle to survive much above 14% ABV.

Whopping big wines like Zinfandel or wines coming from hot growing regions can make for some strong alcohol levels.

Producers working under these conditions often rely on commercial yeast strains that can survive challenging fermentations.

Fermentation Doesn’t Start

Finally, indigenous fermentations depend on yeast doing their thing.

A winemaker can set the juice aside hoping for a native inoculation, but if, for whatever reason, the fermentation doesn’t begin, she’ll need to add a commercial yeast strain before the juice spoils.

There are few things more stressful than waiting for signs that fermentation has started while the juice is at this vulnerable stage.

Where Do Cultured Yeast Come From?

We know humans have been fermenting wine for millennia using ambient yeast. Through the centuries, they discovered that certain fermentation vessels or wineries consistently crafted yummy wines. In a Darwin-esque evolutionary turn of events, some strains had out-competed others.

Scientists isolated these strains and reproduced them in laboratories, noting the yeasts’ particular sensory characteristics on a wine.

Today, major wine labs culture yeast strains taken from wineries around the world for commercial use.

How do winemakers select yeast?

Wine labs that sell cultured yeast have elaborate specification charts. These charts are a lot like vacation rental sites that present different options for you to prioritize: Do you need a place with wifi? How many bedrooms? And my personal favorite: Does it come with a corkscrew? Choices. Choices.

Winemakers weight criteria based on the wine they want to make. Some of the criteria are technical, others sensory.

Once they know what criteria they need to use for the wine they’re going to make, then they go shopping for yeast. Often, they consult with someone at the company who sells the yeast to help them make a good choice.

Let’s look at a few selection criteria.

Wine Yeast Criteria #1: Potential Alcohol Level

There’s good reason to use alcohol for disinfectant. It creates a hostile environment for most living things, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that even our little yeasty buddies have their limits.

Both native and cultured yeast are sensitive to alcohol levels.

Native yeast tend to die off early when alcohol levels reach ±4%-7% ABV. This leaves loads of residual sugar in the young wine just waiting for spoilage bacteria to take over, and is one potential drawback to natural fermentations.

Cultured yeast are selected to survive high alcohol environments.

But even they struggle to reproduce at around 14% ABV.

Big, alcoholic wines, like California Cabernets or Zinfandels that clock in above 15% ABV, need careful paring with yeast strains that can complete the fermentation.

Wine Yeast Criteria #2: Fermentation Temperature

Cultured wine yeast come with temperature ranges indicated in their specifications.

Fresh, aromatic whites, like Sauvignon blanc or Riesling, go through cool fermentations to preserve their aromatics.

Yeast will need to thrive around 55℉/12.8℃.

Red wines have much hotter fermentations to help with color and tannin extraction. The winemaker may choose a yeast that can survive up to 90℉.

Just like humans, if yeast find themselves living a few degrees above or below their optimal temperature range, they’ll have trouble thriving.

Sometimes wineries have little control over temperature. If the winemaker is fermenting in barrel or in a barn, there may be few options for temperature regulation, so selecting a yeast with a broad temperature tolerance may be the best choice.

Wine Yeast Criteria #3: Sulfur and Nutrient Needs

No one wants wine that smells like stinky gym socks. Yeast produce small amounts of sulfides (H2S) as a fermentation byproduct.

Sulfides are responsible for that rotten egg, garlicky, or natural gas smells in wine. Yuck.

Nutrient deficits during fermentation, specifically nitrogen, stress yeast out and can exacerbate this problem.

Specification charts tell you how sensitive a yeast strain is to nutrient requirements and how much sulfide it produces.

Having these details up front will help the winemaker know if she needs to monitor the fermentation process closely.

Wine Yeast Criteria #4: Yeast Killer Factor

Remember those damaged grapes that come into the winery full of who knows what kind of microbes? There’s a yeast for that.

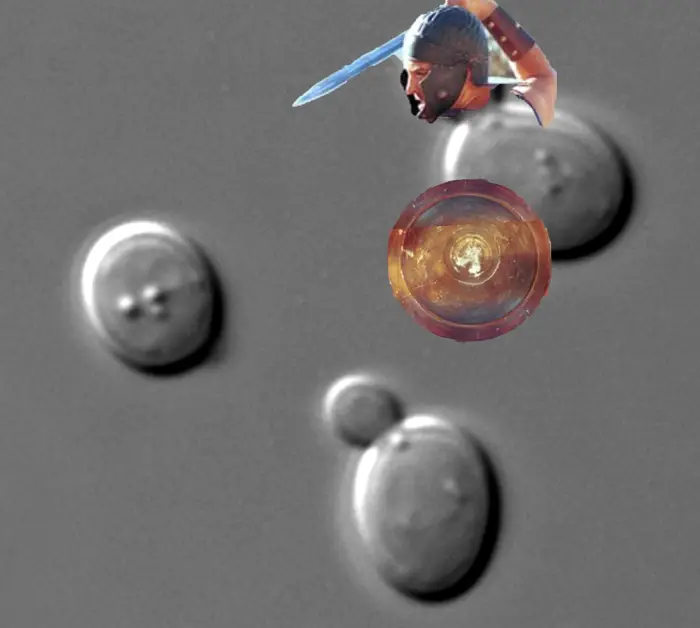

Yeast strains with a high killer factor secret toxic proteins.

The toxins create holes in the cell membranes of other yeast, killing them, and ensuring the cultured yeast dominates the fermentation.

Aside: Whenever I read ‘killer factor’, I picture little bean-shaped yeast cells in gladiator armor.

Wine Yeast Criteria #5: Malolactic Bacteria and Yeast

Another useful technical specification is a strain’s compatibility with malolactic bacteria.

Malolactic bacteria get added to most reds and some whites to help soften and stabilize the wine (more on this later).

What’s important to know is that some yeast play well with malolactic bacteria and some do not. If a winemaker wants to add both the yeast and malolactic bacteria at the same time, then she’ll need to choose her yeast accordingly.

Helpful Tip: Here’s a helpful post that explains malolactic conversion and why your wine tastes like butter.

How to Select Wine Yeast Case Study

Let’s pull everything together. Case Study:

Last year I had a Cabernet Sauvignon that came in late in the season around mid-October. I didn’t have a way to control the fermentation temperature. Fermentation lasted 2.5 weeks, and by then it was early November.

I added my malolactic bacteria, but the young wine wasn’t warm enough to finish malolactic conversion.

This is a problem because you can’t add protective sulfites until malolactic conversion is over.

My wine was vulnerable.

Fast forward to January and I had to get some good-humored friends to help set up several heating blankets, reflective bubble wrap, and heaters to keep the wine warm enough to finish and finally be ready for aging.

Lesson learned.

For the next vintage, I’ll select a yeast strain that’s both tolerant to lower temperatures and can go through co-fermentation with malolactic bacteria at the same time. I’ll add the yeast and the bacteria to the grape juice together.

As you can see, technical specifications play a significant role in yeast selection, but there’s still so much more.

Wine Yeast Selection Criteria #6: Smells, Flavors, Textures

Yeast strains can modify the sensory profile of a wine. They can enhance fruity qualities and even mouthfeel. The best wine yeast elevate the wine’s potential.

Check out these fun descriptors on yeast packaging:

- Respects varietal character, adds complexity and minerality to red wines. A selection from the prestigious Spanish Priorat region. The sensory characteristics include underlying complexity with an overall heightened expression of varietal characters with a good balance between mouthfeel and structure.

- A vineyard isolate from Côtes du Rhône. It is very alcohol tolerant and highly recommended for high sugar reds and late harvest wines. In red varietals, high color and good structure, as well as black cherry, berry and cherry cola aromas.

- The yeast best suited to the fermentation of Chardonnay wines that are fresh, complex and balanced. It is used to highlight fresh citrus aromas (especially lemon), peach, apricot and floral notes. Remarkably, it brings an incomparable amplitude and roundness on the front and mid-palate, followed by a fresh finish for the perfect balance.

With all of these options, how do winemakers choose what yeast to use?

By now you can understand why yeast selection is such a serious business.

But some choices are easier than others.

- Obviously, a natural fermentation takes care of itself. Done.

- House wines are also straightforward. Wineries that produce a label with a consistent style year-after-year will use the same yeast every vintage. Ménage à Trois Red Blend, Yellow Tail Shiraz, Kendall Jackson Chardonnay – we expect these wines to have a particular flavor and aroma profile.

The true art and genius in winemaking, however, lies in selecting strains to complement and enhance the fruit’s natural qualities.

And there’s good news!

Winemakers aren’t limited to a single yeast choice. Wineries can divide up their grape juice into several fermentation tanks and add different yeast strains to each batch.

One strain may help with floral aromatics and another with mid-palate mouthfeel. After the wines are made, the producer goes back and blends them together, creating that perfectly balanced glass.

Yum!

Fun Wine Tip: You now know enough to decipher a yeast specification chart. Here’s an example from Lallemand, a major supplier of commercial yeast, with a checklist of choices.

How to Read Wine Labels for Yeast

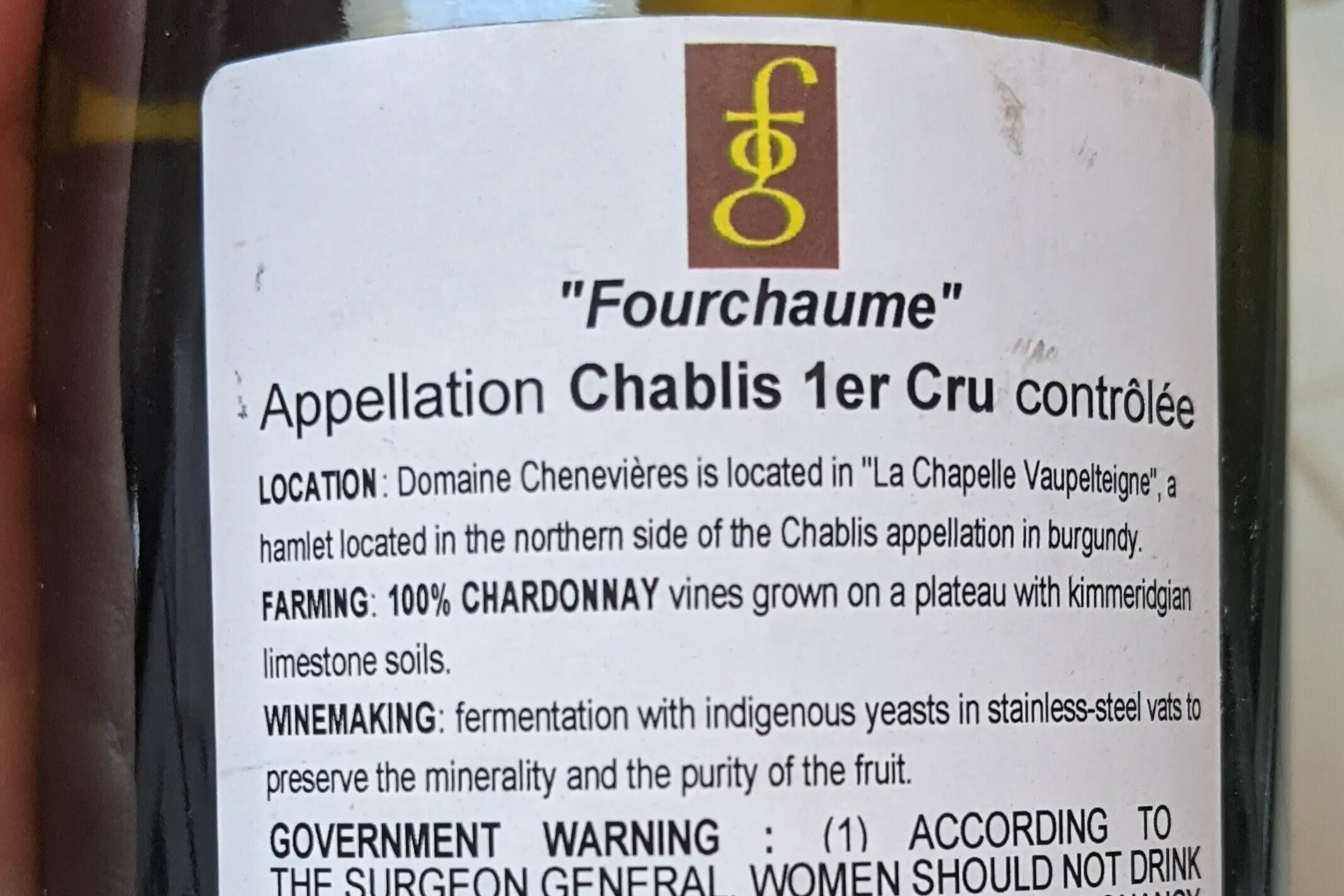

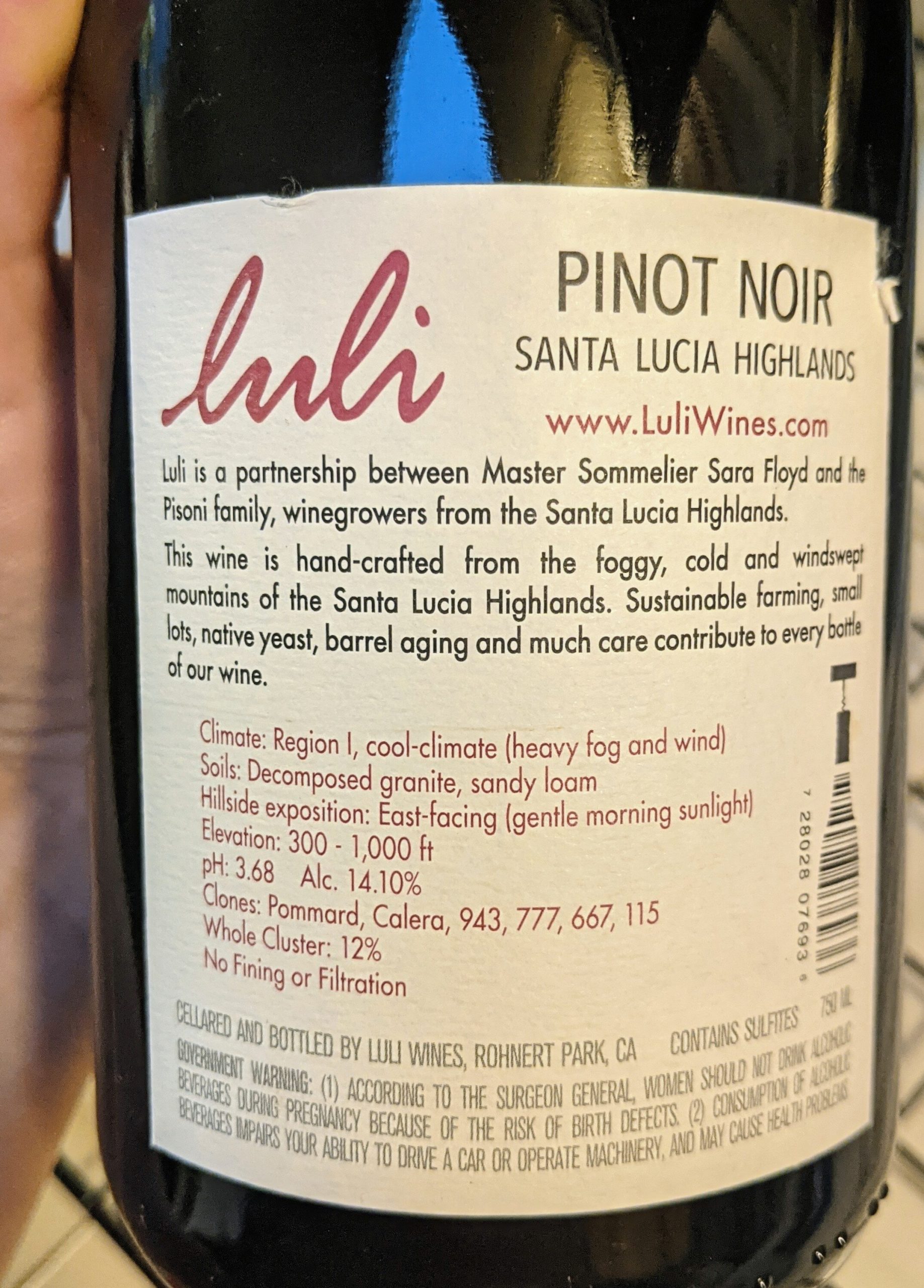

Some wine labels give you clues about the type of yeast they used in their winemaking process. You’ll see words like “native”, “ambient”, or “indigenous”.

Check out this label that sneaks in the words “native yeast”.

Some producers put names like: BDX, RC212, or Prisse de Mousse on the label – these are commercial yeast strains.

There are hundreds of commercial yeast strains, though, so you probably won’t recognize these.

Final Thoughts – Wine Yeast Are the Superheros in Winemaking

Yeast (okay, and grapes) make your wine unique. These mystical, unicellular organisms carry out the magic of fermentation.

The science behind yeast selection and fermentation continues to improve with new discoveries in winemaking each year.

If you want to get a winemaker talking about wine, ask them about yeast. It’s a great way to start a conversation.

Thirsty for More?

If you made it all the way to the end of this post, you’re my kind of wine person! Here’s a fun technical post that explains the difference between press and free run wine.

Aaaand here’s a post I put together on gravity flow winemaking – which sounds new-age, but actually’s been around for thousands of years.