Do you enjoy zippy whites that bite back just a bit? That’s the acid doing its thing.

Tartaric acid occurs naturally in grapes and is the main type of acid that you’ll taste in your wine. Winemakers may add tartaric acid to their wines to help with freshness and stability. Tartaric acid is a safe wine additive, 100% natural, and necessary to create balanced wines.

- What Types of Acid Are in Wine?

- Why Do Plants Produce Acids?

- What’s the Difference Between Acid and pH in Wine?

- What Wines Have Naturally High Acid?

- How Do You Describe Acid in Wine?

- Common Descriptors for Acid in Wine: Acid Balancing Act

- Winemakers Need to Correct Acid Levels to Create Balanced Wines

- Thirsty for More?

What Types of Acid Are in Wine?

90% of the acid in wines comes in two forms: malic acid and tartaric acid. There are some others thrown in that last 10%, but we’ll stick with malic and tartaric. Malic acid is the same acid you find in your Granny Smith apples. Tartaric acid occurs in all sorts of different fruits.

Fruits with Tartaric Acid:

- peaches,

- pears,

- pineapple,

- everything in between

Why Do Plants Produce Acids?

Imagine a fruiting plant trying to ripen its crop. It needs the seeds to be fully mature before the birds and four-legged critters come along and indulge (Side Rant: Deer are not adorable lovable creatures for anyone with a vineyard. They are the enemy.).

High levels of acid serve as a defense mechanism to keep hungry predators at bay.

For grapes, as the growing season progresses and the fruit matures, malic acid levels drop and sugar levels rise, enticing our predators to eat the fruit and, by doing so, to spread the plant’s seeds for propagation.

Imagine the difference between eating an unripe peach and a ripe peach. I know which I prefer!

Tartaric acid levels remain relatively stable during the ripening process and carry through to the finished wine.

What’s the Difference Between Acid and pH in Wine?

A wine has high acid levels if it has a low pH. Lemons have a pH of around 2.0. White wines’ pH is typically around ~3.0. Red wines have a pH of ~3.5. Both water and milk have pHs of around 6.5.

High acid levels protect the wine from spoilage microbes.

Just as our vineyard predators avoid unripe fruit, spoilage microbes find elevated acid levels an inhospitable environment.

This has a couple of implications for wine lovers:

- high acid wines can be aged

- winemakers can use lower amounts of preservatives (sulfites) to keep your wine fresh in the bottle.

What Wines Have Naturally High Acid?

White grapes are generally lower in pH than red grapes, but there are few red varieties that make classic high-acid wines even when fully mature:

- Picpoul (“lip stinger”) (White)

- Riesling (White)

- Semillon (White)

- Champagne (White Sparkling)

- Cabernet Sauvignon (Red)

- Carignan (Red)

- Nebbiolo (Red)

How Do You Describe Acid in Wine?

When talking about acid in the wine, we try to put words to how it feels in the mouth.

What’s the difference between a bite of lemon, a Granny Smith apple, or a sweet tart candy?

All create different sensations in the mouth. The same goes for acid in wines. Think about how the wine changes from the first sip through the back of your throat.

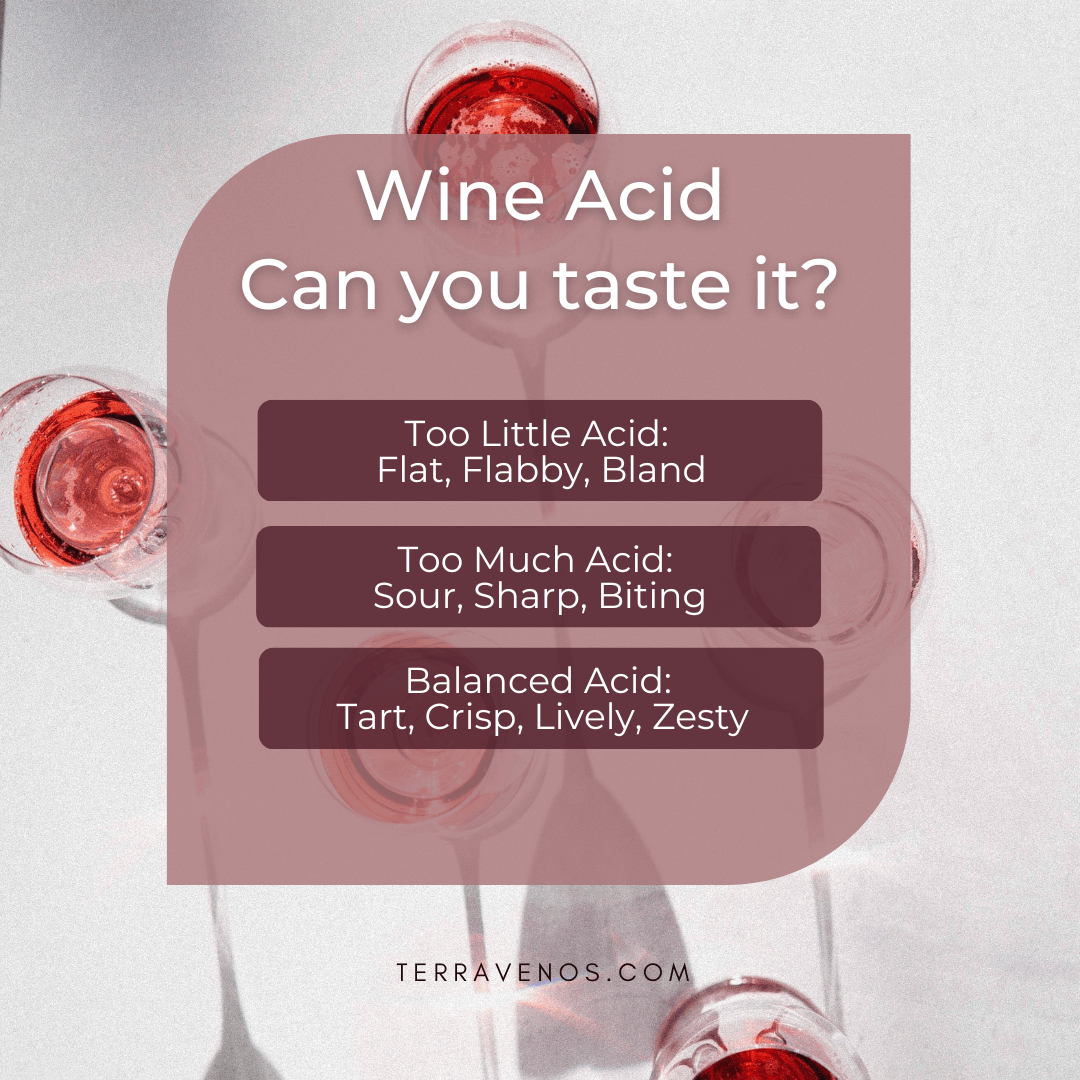

Common Descriptors for Acid in Wine: Acid Balancing Act

Too Little Acid

Wine grapes grown in hot climates, like the Central Valley in CA, tend to suffer from too little acid. If the winemaker doesn’t add acid back to the wine, these wines can end up tasting flat, flabby, or bland.

Too Much Acid

Acid from under-ripe grapes or an out-of-balance wine can end up being sour in your mouth, or sharp, and biting. Sometimes you hear the term ‘over-acidulated’.

Balanced

These wines understand how to integrate all of the sensory components – balancing acid with sweetness, tannin, and alcohol levels.

Wines can be tart, crisp, lively, or zesty.

Acid also balances sweetness. Late-harvest wines, or dessert wines, often have significant levels of acid to keep them from being cloyingly-sweet. High sugar levels mask acid. The next time you sip a dessert wine pay attention to how your mouth waters, a natural reaction to acidity.

Winemakers Need to Correct Acid Levels to Create Balanced Wines

Many variables impact acid levels in wine:

- climate,

- seasonal weather patterns,

- grape variety,

- soil composition, and

- harvest date…

In the timeless words of one of my wine professors, “sometimes you have to be more of the winemaker than the wine shepherd.”

Remember that of the 2 main acids, malic and tartaric, malic will decrease in strength through the growing season. The vine actually converts malic acid into sugar to help it through the final, hottest stages of the summer.

In very hot climates, grapes can arrive at the winery with insufficient acid levels.

Wineries are legally permitted to add acid to help balance out the wines.

Did You Know? manufacturers produce bulk tartaric acid for all sorts of food production uses, not just wine – baking powder being a big one.

The reverse can happen, too.

In unseasonably cool years, those same grapes can come into the winery with too much malic acid. In this case, wineries can use a microbiological process, called malolactic fermentation, converting the sharp malic acid (green apples) to a softer lactic acid.

They can also correct high acid levels by adding alkaline to the wine, for example, calcium carbonate – literally the same chemical in Tums or the antacids you use for an upset stomach. Which creates a hugely entertaining mental picture.

What’s the relationship between tartaric acid and tartrate crystals?

Tartrate crystals, a.k.a. wine diamonds, are nifty evidence of wine chemistry in action.

Stay with me: Acid comes in different ‘species’.

The tartaric acid can form potassium bitartrate (salt crystals) when it binds with potassium in the wine and falls out of solution.

How does that happen? The wine gets cold.

Sustained cold temperatures cause a chemical reaction between the tartaric acid and the potassium forming the ‘wine diamonds’, or crystals, that lead to a snow globe effect in the wine that almost look like small glass shards.

A good winemaker will cold stabilize their wines before bottling to prevent this from happening. Cold stabilizing involves chilling the wine to about 30℉ for about 3 weeks, forcing the chemical reaction to happen at the winery, instead of the consumer’s dining table.

Wine diamonds are more noticeable in white wines – cuz they’re transparent – but can happen in any wine.

And thus you have a completely harmless but fascinating bit of chemistry to contemplate while swirling your glass.

Thirsty for More?

If you like wine chemistry, go to this post on wine fermentation, and here’s one on what sediment means in wine.

And if you’re more into the economics of wine, here’s a lengthy explanation of how wine bottles get priced.